Hello everyone, hope you all are doing great. I’m planning to write some blogs (you can call it a series of blogs) on Buffer Overflows. I will be posting all of them one by one in the coming weeks. Since we will be smashing the stack when doing buffer overflows in the upcoming blogs, it is crucial to first have some knowledge on some of the basics. So, let us begin with some introductory topics. We will be using 32-bit 8086 architecture during these blogs unless explicitly mentioned.

The stack. What is it?

In computing, the stack is a linear data structure. The data is stored in a Last In First Out (LIFO) order. Imagine the stack as a pile of coins. We can only remove (POP) the coin at the top and if we were to add another coin to the pile (PUSH) , we’ll have to insert it to the top of the pile. A little caveat here — the stack grows towards lower memory addresses. This means that the bottom of the stack is at higher memory address and the the top of the stack is the lower memory address.

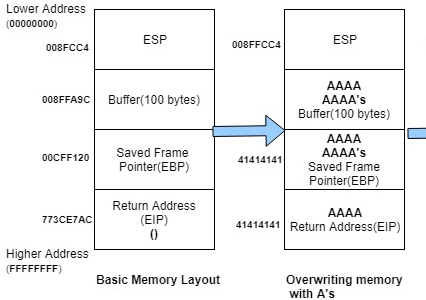

Memory layout before and after overflow. [ Source ]

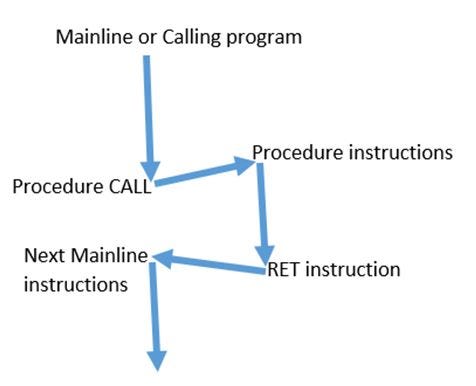

A compiled program will contain multiple functions at different parts of the stack. The function’s executable code is placed in a fixed region of memory at the start of the program and persists undisturbed until the kernel unloads the program after it exits. Data will be passed from one function to another during the execution of the program so the Operating System needs a way to track these functions. Each of these functions will in turn have their own local variables, arguments, etc,. and we need to store these in memory to be able to access them during runtime. This is done with the help of the stack frames. Each function has their own space in memory called its stack frame. When a function is called, a new stack frame is allocated in memory for that function’s storage needs and then when the function is complete, the frame gets de-allocated. In the stack frame, the function’s return address is pushed into the stack first and then the arguments and space for the local variables for that function.

Let us take a quick detour and learn about Registers quickly

Registers

Processor operations involve processing data. To process the data, we first need to access the data from somewhere. We can access the data from the memory. However, reading from memory slows down the processor as it involves a lot of complicated steps. To speed up the processing, we have registers which are special memory storage locations in the processor itself. These are faster than normal memory. These registers store data elements without having to access the memory.

We will only discuss three of the important registers namely:Instruction Pointer (IP): This register contains the address in memory of the next instruction to be executed

Stack Pointer (SP): This register points to the top of the stack.

Base Pointer (BP): This register is used to access the arguments and local variables. It marks the start of the function frame

The return address

When a function such as printf() is called, it stores its current position in memory on the stack before continuing its execution. This is done so that the program can return to the last position in memory it was before and continue execution after the function is executed. The return address is an integral part when discussing buffer overflows. It can be used to control the execution of the program by diverting the control flow of the program. If we can somehow manipulate the return address, we may be able to control the execution of the program and make it do things it shouldn’t do!

Endianness

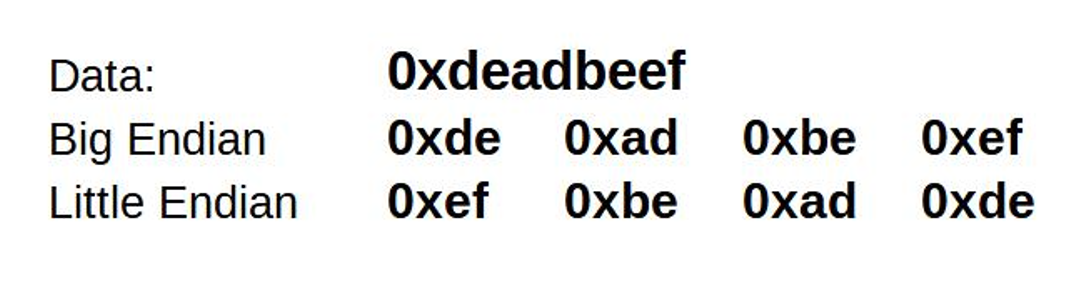

Bytes are read and ordered differently in different architectures. Endianness describe whether the most significant or least significant byte is ordered first in a multi-byte value. We have two types of endianness:

Big Endian: The most significant byte is stored at the low memory end.

Little Endian: The least significant byte is stored at the low memory end.

Big Endian vs. Little Endian

To represent an address (say 0xdeadbeef) in Big Endian format, we will have to write it as it is (0xdeadbeef). But when we use Little Endian, we have to flip the ordering of the bytes (0xefbeadde).